| The

emerald ash borer:

tiny, green, deadly

By Dan Blouin

OTTAWA —

The emerald ash borer seems

just like a plain old bug. It looks a bit like a grasshopper.

It's bright green and no bigger than a penny.

But this bug has cost Canadian and U.S.

forest industries millions of dollars — it's the

focus of many lives. Including Ken Marchant’s.

Marchant is a plant protection officer

with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. His job description

says it all — he protects plants. And for the

past three years, he's been trying to do it by chasing

a tiny green bug around Southern Ontario.

The bug is winning.

| 'Beetles

like this are not supposed to be killing trees like

this.' |

"It's certainly the zebra mussel

of the land," he says. "Beetles like this

just are not supposed to be killing trees like this.

It is a classic alien invasive species."

It began a few years ago, when people

in Michigan started noticing that a lot of healthy ash

trees were suddenly dying.

And no one knew why.

But then in 2002, forestry officials found

a little green bug. One that no one had ever seen before.

"...where did this thing come from?"

he says. "That was one of those things that tweaked

us at the beginning...eventually a specimen was found

in a Czech insect institute."

The insect, they learned, was called the

emerald ash borer and is found all over eastern Asia.

Marchant says locating it here in North America was

— and still is — a real problem.

"It is extremely difficult to detect,"

he says. "It doesn't have any pheromones. We still

don't know after three years how it finds the ash. It's

a fairly cryptic little guy, it doesn't fly around in

big swarms, so it's hard to miss it."

Marchant says the ash borer probably came

over to North America in packaging materials. He says

shipping crates are often surrounded with wood chunks

or chips to prevent them from sliding around on ships.

New laws require wood coming into Canada and the U.S.

to be fumigated and heat-treated, which would kill any

dormant eggs. Marchant admits, however, that it's impossible

to inspect every stick of wood.

But to find out how to stop the ash borer

now, Canadian scientists needed to learn more about

what made it tick. So they went to the source.

"We sent teams of scientists to China

to look at the problem. And there's virtually nothing

in there...it is simply not a problem there."

What they did learn was bad news. The

ash borer lays it eggs in the bark of the tree where

they hibernate over winter — so Canadian cold

won't kill them. When the larvae hatch in warmer months,

they eat the outer wood under the bark, forming tunnels

that disrupt the movement of water and nutrients inside

the tree. After two or three years, the tree dies.

Emerald

Ash Borer gallery

|

| The ash borer larvae burrow

through the softer layers of the tree, forming galleries

like the one shown here. (Photo courtesy of the

Michigan Department of Agriculture) |

So why wasn't it a problem in Asia?

Barry Lyons, a research scientist with

the Canadian Forest Service, says it's all about natural

resistance.

"Lots of plants produce what are

known as secondary chemicals that are produced in response

to insect pests . . . and when insects evolve with a

host plant, there's kind of an escalating arms race

going on. The plant produces a new chemical and the

insect develops a resistance to it and so on."

Lyons says these natural insecticides

force these kind of insects to be opportunists —

they can only infest trees that are already weak or

dying and can't produce the chemicals.

But North American trees only develop

resistance to North American pests. Asian insects like

the borer aren't affected by their natural chemicals.

It's the same way smallpox devastated Aboriginal populations

during Western colonization — without natural

resistance, even the healthy get sick and die.

"The ashes here just don't have the

natural blend of chemicals to fight them off that a

tree that had developed alongside it would have,"

he says.

Another problem with foreign pests is

that native predators — like woodpeckers or wasps

— don't recognize the borer as being edible. With

time, they may develop a taste for the bugs, but Marchant

says only about two per cent of the ash borer population

is being killed by other animals right now.

So this means the ash borers are free

to breed and grow and spread. Stopping that spread is

Marchant's main goal — to halt its progress until

they learn more about the ash borer and how to kill

it.

The stakes are fairly high. According

to the Oct. 14, 2003 edition of the U.S. Federal Register,

Michigan has lost over $13 million in wood sales alone.

Replacing lost trees could cost up to $11.7 billion.

The register estimates up to $25 billion in losses if

the ash borer spreads to other eastern states.

And it is already coming north.

When the CFIA started fighting the ash

borer, the first step was a quarantine. In October 2002,

the CFIA banned the movement of ash into or out of the

Windsor area. That would ideally stop humans from unknowingly

spreading the borer, but it would continue to do so

on its own.

| 'The biggest

risk is that somebody's going to be visiting their

daughter in Essex or whatever, load up their car

with firewood and drive back to Lanark ... we won't

know until it happens, and almost by the time you

find it, it's too late.' |

Canada had an opportunity the Americans

couldn't take advantage of. The borer was moving east

from Windsor through Essex County, and was spreading

north into the rest of Ontario. But first it would have

to pass through a relatively thin stretch of land between

Lake St. Clair and Lake Erie. It was there that the

CFIA decided to make its stand.

The idea was to create a kind of fire

break.

"The Americans never got the breakwall

up; they could never really find the leading edge (of

the spread)," Marchant says. "The Canadian

geography was so much of an advantage, with the St.

Clair Lake and Lake Erie, and you're dealing with one

of the most treeless land zones in eastern North America.

. . the place is only about 0.8 per cent tree cover."

The CFIA planned to stop the ash borer

in its tracks by eliminating its food supply. In late

November 2003, the CFIA announced that all ash trees

and materials would be removed from a 10-kilometre-deep

swath of land from Lake Erie to Lake St. Clair. The

CFIA also ordered that firewood of all types would not

be allowed to leave the ash-free zone, to prevent people

from confusing one type of firewood with another.

"At the time we thought probably

five kilometres is the maximum it could spread by itself,"

Marchant says. "The initial recommendation was

five kilometres, but after looking more at this we decided

to go with 10."

The logic is simple. If the ash borer

can only fly five kilometres in search of food before

it dies, and if it is surrounded on three sides by either

water or land without ash, they would only be able to

go back the way they came. And Marchant says that Essex

County was already beyond saving.

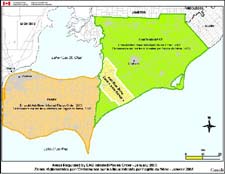

Map of the Ash-Free

Zone

|

The faint

yellow area shows where the ash-free zone was

cut, all the way across from Lake St. Clair to

Lake Erie.

(Photo from the Canadian

Food Inspection Agency) |

"All of the horror stories about

what would have happened to Essex if the emerald ash

borer got loose all came true. It was one of those things

where we would have loved to be wrong," he says.

But they weren't. Marchant says about

80,000 trees were cut down and either burned or trucked

out of the zone over the winter. As spring came around,

they were on the lookout for any infestations on the

other side of the zone.

And they found them. Marchant says some

break-jumpers were expected.

"No one ever said this would eradicate

the beetle. We expected it to slow the spread and keep

the outliers — and we knew there would be some

— manageable...in a perfect world, it would have

worked."

Things haven't worked out the way they

were supposed to. The ash borer has been found in Chatham-Kent

County north of Essex and the ash-free zone in populations

much higher than expected. He says it's because people

ignored the quarantine.

"These were all the result of human

activities. Ninety per cent of them at least can be

attributed to human activities. There was someone who

had been moving and selling firewood in their backyard,

and there was a small unregistered sawmill."

The CFIA has since issued another quarantine

to Chatham-Kent and another 34,000 trees are supposed

to come down before May.

"The actions we're taking now are

going to have a major impact on it," Marchant says.

"Without it, the population in Chatham-Kent will

explode. Seriously explode, based on what we've seen

in Michigan and Essex."

John Enright, a forester with the Upper

Thames Conservation Authority located north of Chatham,

says there haven't been any sign of emerald ash borer

infestations in his jurisdiction, but says he keeps

up-to-date on the latest news. He adds preparations

are in place in case the ash borer is found.

"People have been contracted again

to remove those trees and any ash within 500 metres,"

he says.

Marchant says there is progress being

made on pesticides, but it's impossible to rely on them

to solve the ash borer problem.

"There's about a billion ash trees

in Ontario, that's a conservative estimate, and most

of them are forest trees. There's no way you could ever

treat them all," he says. "The only real way

that this thing is going to come into balance is that

there are some resistant trees are going to show, and

that's probably just because they won't taste right.

. . that or a natural complement of parasites and predators."

When other predators start eating the

bug in large numbers and trees develop defences, the

ash borer will then be just like any other native species.

Until then, the CFIA is relying on the

fire break to slow the emerald ash borer's spread. But

unless people obey the quarantine, it could reach other

parts of Ontario, leading to another outbreak - this

one without the natural barriers the CFIA took advantage

of initially.

"The biggest risk is that somebody's

going to be visiting their daughter in Essex or whatever,

load up their car with firewood and drive back to Lanark,"

Marchant says. "We won't know until it happens,

and almost by the time you find it, it's too late."

Lyons says people just don't appreciate

how dangerous the ash borer really is.

"There's nothing exactly comparable

to this one. This is a very aggressive tree-killer.

It seems to disperse very quickly, whether through its

own means or through humans spreading it, and I suspect

the latter. . . it's like nothing we've seen before."

He adds people need to understand the

wider importance of trees, beyond just the forest industry.

"Trees are incredibly important things.

. . All of the things that trees do, sequestering carbon,

cooling houses, air pollution controls, all of these

things are very important."

"People in the rest of Canada probably

have never heard of the emerald ash borer and don't

know it's a threat right now."

To them, it's just another bug.

|