| Big

Brother is scanning you: Biometrics

goes mainstream

By Ben Singer

OTTAWA —

An employee stands nervously

as the unblinking lens of a wall-mounted camera silently

scans his face.

Software controlling the camera looks

for key features and converts them into digital code.

In milliseconds the camera generates a template and

sifts through a database in search of a match. A green

light comes on. The man has been identified as an employee,

and unfortunately for him, one who is 15 minutes late.

Bummer for the late man. Boon for his

bosses.

The example is demonstrative, but the

technology is very real. It’s called FaceCam,

and it's made by an Ottawa company called VisionSphere

that specializes in facial recognition technology for

companies and law enforcement agencies.

|

| FaceCam is a biometric product

made by Ottawa's VisionSphere Technologies. |

It's one in a growing list of Canadian

companies that have jumped on the biometrics bandwagon.

Until a few years ago it was mainly the

stuff of movies, but biometrics – the science

of automatically identifying people based on unique

traits – has rapidly become commonplace. Machines

that can I.D. a person from their face, fingerprints

or eyes, are scanning away in businesses, homes and

airports.

Biometrics has been around for centuries

in low-tech forms. But since September 11, 2001, new

biometric technologies has left the lab and entered

everyday life.

Old idea, new technology

The Chinese figured out how to tell babies

apart by making ink impressions of their feet 700 years

ago. Europe didn’t develop fingerprinting until

Scotland Yard began using it in the early 1900s. Modern

technologies like iris and face recognition began popping

up in the 1980s. But it took the disaster of 9/11 to

bring biometrics to the forefront.

|

| Sir Edward Henry created

the first fingerprinting system in 1900 for Scotland

Yard . |

After the attacks, the U.S. passed laws

like the Patriot Act, and the Aviation and Transportation

Security Act, which mandated the use of biometrics as

a tool to find and stop terrorists and criminals.

Hi-tech companies got in on the act quickly.

By 2002 the global biometrics industry was worth about

$600 million. This year it took in $1.4 billion, and

it is projected to reach $4 billion by 2007.

Today, elementary school kids in Pennsylvania

buy lunch with automated fingerprint scanners that deduct

money from their accounts and the state of Florida books

criminal suspects into jails using facial recognition..

Canada has been slower to embrace biometrics

than our southern neighbour.

“We’re behind in many ways,

some of which are important, some of which aren’t,”

says Andy Adler, a biometrics researcher at the University

of Ottawa.

Adler, who cut his teeth developing scanners

and encryption software for biometrics companies, is

a supporter of the technology, but admits not every

application is worthwhile.

“Biometrics for school lunches is

stupid,” he says. “It costs far more to

put in a fingerprint system than it does to just deal

with the fact that the occasional student will take

an extra lunch.”

| 'I’m a firm

believer that biometrics is a good thing for governments

to keep. There’s bad people out there and

we need to use the technological tools we can to

try to find them.' |

Where it’s worth the expense –

like restricting access to a company’s computer

network, or preventing terrorists from crossing the

border - Adler says biometrics can play a key role.

“I’m a firm believer that

biometrics is a good thing for governments to keep,”

he says. “There’s bad people out there and

we need to use the technological tools we can to try

to find them.”

The Canadian government is starting to

get that message, thanks in part to a push from the

south. One American stipulation after 9/11 was that

countries whose citizens didn’t require visas

to enter the U.S. must now develop passports with biometric

information to maintain that status.

Canada’s passport office

has not made that change yet, but in 2003 it completed

a pilot study of facial recognition, which according

to the office’s website, “definitely confirmed

the value” of the technology. And the same year,

new passport photo requirements made smiles, bad lighting

and fuzzy focus verboten: those factors reduce

the ability of a machine to ‘read’ the photo.

Matching mug shots

Some law enforcement

agencies have been quicker off the mark. The Canadian

Police Research Centre began a project in 2002 to implement

facial recognition in the booking process.

Project BlueBear, which used VisionSphere’s

technology, lets police match suspects with mug shot

databases from multiple police departments.

Andrew Brewin, CEO of BlueBlear Networks

International, a law-enforcement spin-off of VisionSphere,

says the project was a success, and the company is working

on commercializing the technology.

Brewin says BlueBear uses facial recognition

because unlike other biometrics, it can make use of

the large photo databases that already exist.

“Being able to make use of those

mug shots and other facial databases and obtaining pictures

of people is an awful lot easier than getting their

fingerprints,” says Brewin.

He says that if his technology has been

in use in U.S. airports, at least one 9/11 hijacker

would have been identified and stopped.

Facial recognition is one of the big

three biometrics in wide use, beside iris and fingerprint

systems.

All three operate on the same principles.

First, an image of some feature unique to an individual

is captured. This could be the ridges and folds of a

fingerprint, the patterns of the iris, or certain facial

features like the distance between eyes.

Once the features are captured, they

are converted to digitally encoded templates, and stored

in large databases on computers that, at least in theory,

are secure.

When a person wants entry to a restricted

area, or access to a computer, he allows a scan of whatever

feature is needed. That digital template is then matched

to the existing database to verify if that person is

who he says he is, or whether or not he is on the list.

Biometrics finding everyday uses

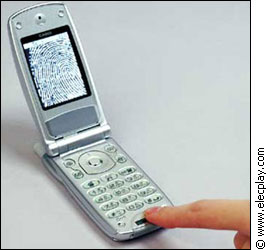

Seemingly mundane uses for biometrics

are becoming more and more popular. IBM laptops allow

people to log on without worrying about passwords or

codes; some Japanese cell phones are equipped with fingerprint

scanners to deter phone theft.

|

| In Japan, some cell phone

are equipped with fingerprint scanners to deter

thieves. |

Fingerprint scanners come in two varieties:

optical scanners, which work by the same principles

as digital cameras, and capacitance scanners which use

electrical currents.

With optical scanners, the subject places

their finger on a glass plate, while a digital camera

with a light source shines light on the print, and photoceptors

measure the reflected light. A negative image is obtained,

with dark lines representing the ridges and light lines

representing the valleys of the print.

Capacitance technology uses a semiconductor

chip with many tiny pairs of conductor plates. Each

pair can detect how far the conductive skin of the finger

is from the plates as a difference in capacitance. This

way it can tell a ridge from a valley and convert this

into a detailed fingerprint image. Unlike optical scanners,

capacitance requires a real three-dimensional fingerprint,

and cannot easily be fooled by a photo.

Facial recognition really just requires

a camera and software.

BlueBear’s Brewin says that facial

biometrics is popular because it is up to 10 times cheaper

than fingerprint technology with its expensive scanners.

A facial recognition system uses a high

definition camera which adjusts itself to center on

the face, while the computer searches for pre-designated

features. Hard tissues like eye sockets, the bridge

of the nose and the jaw are used because they are difficult

to alter, even with plastic surgery.

Those features, called nodal points,

are measured by the system and converted into a numeric

code called a faceprint, which can be matched with other

faceprints in a database.

Some facial recognition systems are able

to work from a distance, using surveillance cameras,

or even photographs – unlike iris and fingerprint

scanning which require a subject to submit to a scan.

With accuracy rates around 92 per cent,

face recognition is probably not good enough for the

highest security uses. But Brewin says his labs are

working on the latest development – 3D facial

scanning – which he contends will revolutionize

the industry.

3-D revolution?

|

| New 3D biometrics offers

the potential of higher accuracy. |

The 3-D system uses pairs of closely-spaced

cameras to record different angles of a face. Millions

of tiny visual features are captured from every angle

and triangulated or processed to determine the distance

of each from the cameras. Computer algorithms, a set

of binary instructions, “connect the dots”

to render a three-dimensional model of the face, which

can also be called up by a human operator to verify

who is standing in front of them.

Ideally, 3-D technology would increase

accuracy, but researcher Adler is unconvinced of the

merits of 3-D and other new biometric technologies.

“New is not necessarily better,”

he says. “New is suspicious.” But he adds

that these unproven technologies will find homes in

places like retail stores, where novelty trumps reliability.

The third major biometric in wide use

is iris scanning. Considered one of the most accurate

technologies, iris scanners can identify up to 266 unique

features — almost triple the fingerprint standard

of 90.

|

| The striations and patterns

of the iris are a powerful biometric identifier.

|

Iris scanners take a black and white picture

of the eye from up to a metre away, using a non-harmful

near-infrared light.

Algorithms determine the boundaries of

the iris, and through a process called demodulation,

converts the unique iris features into a digital code

that can be stored and compared with others.

Air passengers can see iris scanning

at work in some Canadian airports, under the CANPASS-Air

program. The Canadian Border Services Agency program

allows people to sign up for a fee, and after a background

check they can have their irises scanned. When returning

from out of the country, CANPASS members simply look

into a scanning kiosk, and once verified, skip through

customs without waiting in line.

The accuracy of iris biometrics means

the number falsely accepted will be almost zero, but

Adler points out that the technology may falsely reject

some people who are in the database.

Spoofing the scanners

Despite the increased presence of biometrics,

the integrity of the technology has been questioned

by “Black Hat” researchers, who have shown

how to ‘spoof’ or trick scanners with photos,

videos or – in one famous case – fake fingers

made of gummy bear material.

For this reason, many companies now incorporate

‘liveness detection’ into their systems.

“One of the things we do is we make

sure there is some movement when we’re taking

the picture, so we know it’s a person –

there’s somebody real in front of the camera,”

says Brewin. “But you could still use an LCD screen,

for example, to trick it.”

Other liveness detection methods include

fingerprint sensors that measure blood oxygen levels,

or look for a pulse, but few are that ambitious.

Rene McIver, director of technology at

Bioscrypt in Mississauga, says the company’s fingerprint

technology is immune to some attacks, but it’s

not spoof-proof.

“Your finger has conductive properties

to make (scanning) happen,” she says. “Not

all materials have that property, and so you would have

to make sure that the material that you were using to

create a fake finger would have that property for this

particular sensor.”

|

| Hand scanners are appearing

in offices and stores, for employees to sign in. |

Bioscrypt has contracts with the Canadian

Aviation and Transportation Security Association and

the U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security.

McIver says the key to the company’s

success is the software they use to match prints to

a database.

Unlike most programs which reduce the

fingerprint image to a set of defined ‘minutiae’

– like ends or bifurcations in ridges –

Bioscrypt’s pattern algorithm reads the whole

fingerprint.

McIver proudly boasts that Bioscrypt’s

algorithm won first prize at the Fingerprint Verification

Competition in 2002 and 2004, outperforming all other

industry and academic players.

| 'I’m pointing

out there are flaws in the encryption strategies,

and it’s possible to get information out of

these systems that you might not think are possible.' |

But some researchers caution that

using entire patterns – instead of discrete minutiae

– could allow a hacker with time and dedication

to recreate the print. Andy Adler recently demonstrated

this in facial recognition. Using a technique called

‘hill climbing,’ Adler reconstructed key

features of a face in reverse from a digital database.

This, despite some developers’ insistence that

it was impossible.

Adler is cautious about his findings,

saying, “I haven’t by any means pointed

out that these things don’t work, or that they’re

really wide open.

“What I am concerned about is there’s

very little researchers like me who are looking for

the problems . . . I’m pointing out there are

flaws in the encryption strategies, and it’s possible

to get information out of these systems that you might

not think are possible.”

McIver, who works with Adler on standardizing

the biometric industry, says that Bioscrypt is developing

new encryption techniques to prevent abuse or theft

of people’s information. But she adds that people’s

concerns about protecting something as easily available

as their fingerprints may be misguided, asking, “Why

would we try to hide that unnecessarily, when you can

go and grab it off a glass?”

Nowhere left to hide?

While Adler and McIver see biometrics'

benefits — from security to convenience —

some question its increasing use.

Organizations like the American Civil

Liberties Union cried foul when it was revealed that

police used facial recognition surveillance systems

to scan fans at the 2001 Super Bowl.

In Canada, concerns have been raised over

the potential use of biometrics in identity cards for

immigrants and refugees.

Ian Kerr, a law professor at the University

of Ottawa, says racial profiling and invasion of privacy

are issues that should be discussed when making the

decision to use biometrics.

"The use of biometrics is just one

more example of what has seemingly become a kind of

fetish practically, for identifying people for all sorts

of things,” Kerr says.

“The real question to ask is what

is the purpose to identify and sometimes we build a

sort of false sense of security around the need to identify

people, but really, many of those technologies lead

to all kinds of ill consequences.”

Brewin, CEO of BlueBear, says he is concerned

about privacy issues, “both as a Canadian and

as a businessperson.” He defends his company’s

law enforcement products, which he says provide, “the

ability for the individual police departments that own

the data to ultimately control who sees it, and what’s

allowed to be seen of it.”

And while Adler is concerned about abuses

of biometrics, he doesn’t see the technology as

the culprit.

“The issue is that the governments

aren’t trustworthy with the data,” he says.

“The biometrics of lack of it isn’t going

to stop that core privacy invasion issue.

“I’m concerned about it, but

I don’t actually see biometrics as the core evil

here.”

|