|

Scientists working at the Canadian Forest Service’s Atlantic Forestry Centre are in the process of wrapping up a five-year program, which they hope will yield “elite” plants capable of rapid growth and increased taxane production. In response to stress, such as insects and drought, these plants produce chemicals called taxanes that can be used to make certain cancer drugs. Growing up to two metres in height, the Canada yew belongs to a species of shrubs that have anti-tumour properties. These elite plants would help minimize overuse and aid in satisfying the demand for taxane-based cancer drugs. “Right now, Taxus canadensis is a good source,” says Stewart Cameron, a tree physiologist with the Atlantic Forestry Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick. “The process of extraction and processing is easier.” From shrub to drug Scientists discovered in the 1980s that the Canada yew’s reddish-brown bark also had anti-tumour qualities and could be used to make a cancer drug called paclitaxel.

Paclitaxel is a chemotherapy most commonly used to treat ovarian, breast and non-small cell lung cancer. It works during cell division to slow tumour growth by binding to the cell’s skeleton, or what are called microtubules. According to Cancer Care Ontario, in randomized trials where paclitaxel was used to treat patients with metastatic breast cancer, the overall rate of response to treatment was on average 40 per cent. The problem is not with the drugs effectiveness, but with finding a way to accommodate the increasing demands for this cancer drug. Keeping up with demands Ron Smith, a retired tree physiologist who works alongside Cameron, estimates that it takes 30,000 kilograms of Taxus biomass – the mass of Canada yew before processing – to produce one kilogram of Taxol, a brand name of paclitaxel. Industry reports for 2005 put the demand for Taxol in North America and Europe at approximately 400 to 500 kilograms, Cameron says.

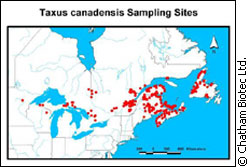

With these calculations, it would take between 12 and 15 million kilograms of biomass to meet this year’s demands for Taxol in North America and Europe alone. And when it takes a large amount of biomass to extract a small amount of taxane, the drug costs become significantly higher. “You could treat 33 people with a tractor-trailer load of green biomass,” says Eric Smith, the research co-ordinator at Chatham Biotec Ltd., the largest supplier of Canada yew product in North America. “We’re hoping in the future that we can lower the growing cost,” says Eric Smith. If the biomass can be produced at a lower cost, notes Cameron, it becomes more competitive on the world market. Finding the best of the best As part of their research, Cameron and Ron Smith visited sites throughout Eastern Canada and the United States. They returned to their lab with around 1300 clones – or exact copies of Canada yew plants found at different sites.

Each plant then had to be isolated and grown in the same controlled environment before researchers could begin to determine how fast each plant grows and how much taxane each plant produces. This process is called a range-wide provenance trial – plants are gathered from a wide selection of sites and grown in the same conditions. While initially using cuttings, scientists moved to a process called somatic embryogenesis. This process, which uses an in vitro tissue culture technique, allows scientists to quickly produce scores of genetically identical plants. Eventually, out of the plants the team will select between 10 and 50 elite clones. Work on the project should be complete by 2008.

As part of an agreement made in 2002, Chatham Biotec Ltd. has largely funded the estimated $2.1-million Canada yew project – paid out of their harvesting profits. "We're getting a lot of good results," says Eric Smith's son Derick, the plantation manager at Chatham Biotec Ltd. "Now it's just a matter of fine tuning." Derick Smith guesses that it will be about one to two years before they can start to get cuttings off the new plants. Playing by the rules The research team, alongside the Canada Yew Association, set out voluntary guidelines to follow when pruning the slow-growing shrub. The association’s members include representatives from government, industry, research facilities and environmental organizations.

“You want to cut them at a level so that the plant is still very healthy,” says Ron Smith. Ron Smith compared sustainable pruning to getting a paper cut. A paper cut heals in a short amount of time, but a severed finger – once re-attached – would take much longer to heal. The guidelines for sustainable pruning recommend that only six to eight inches should be cut every four to five years. The recommendation is to cut into the green area of the stem to ensure only three years of growth are removed from a plant. On a whole, Derick Smith says the initial goals the project set out to meet have been largely successful – especially the sustainable harvest guidelines. "We’re really happy with what's been accomplished," says Derick Smith. “We’re hoping it will shape the industry.”

|

|

|