|

It is also typical of what most people associate with all corals reefs; a tropical locale, warm shallow waters and brilliant colours. However, coral reefs exist in the cold, deep and dark waters of the northern hemisphere as well – in fact, two-thirds of all known coral species are found in depths of up to 1,500 metres, and at temperatures around one degree Celsius.

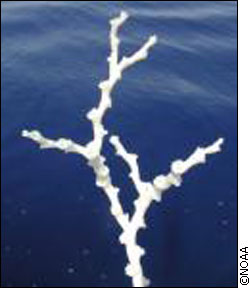

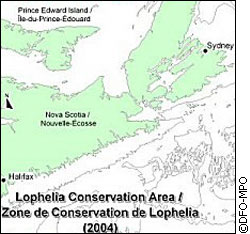

These cold water corals, which are also known as deep-water corals, are different from their tropical counterparts — they don’t need sunlight to live, for example — but similar structurally in that they provide habitat for countless other species. Although Canadian waters are home to over 20 species of deep-water corals, the only known reef building type found here is called Lophelia pertusa. It’s one of the most common reef building deep-water corals in the world. The reef in brief "A reef is a structuring habitat," says Evan Edinger, a geography and biology professor at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. "It’s not a geographical feature, but it is an actual geographical build-up." That build-up takes thousands of years. Reefs grow very slowly over a long period of time - in any given year one might grow only 20 millimetres or less. The reef itself is a network of individual coral polyps whose skeletons form the underlying structure. Polyp skeletons, which make up the majority of a reef, are comprised of calcium carbonate; the same compound as limestone. "Think of it like a long straw,” Edinger says. "Coral, as they grow, the skeleton gets longer, and as it elongates it leaves skeleton behind. The top ten to thirty centimeters of a reef is comprised of live Lophelia, but below that is just dead skeleton." Looking for lophelia Lophelia reefs have been identified and protected in an area called the Stone Fence, in the very northeastern corner of the Scotian shelf, just off the coast of Nova Scotia. There is also evidence to suggest there are Lophelia corals off the coast of Newfoundland, says Edinger, and on the West coast as well.

"There are some new discoveries from off the coast of Vancouver Island and northern Washington, but there is still very little data available," says Edinger. "Most of the research there is primarily studying [sea] sponges." One of the reasons coral research has been limited is because of the time and cost involved, says Marty King, a conservation expert with the World Wildlife Federation of Canada. "The problem is, we just don’t know where the rest of these places are," says King. "Unfortunately it’s incredibly expensive research."

However, with an ever-increasing body of knowledge, researchers now at least have a better idea of where to look for corals. Ocean topography is as varied as the land. Underwater mountains known as seamounts, as well as channels and continental shelves provide good conditions for all corals, not just Lophelia. Fish friendly Because corals are passive feeders — that is, they wait for food to come to them - they thrive in areas with strong currents that can carry lots of food particles past, while at the same time removing smothering sediment. This preference to live near fast-moving water is partly what makes coral an important habitat for fish, says Dr. Daniel Pauly, professor and director of the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. It takes energy for fish swim against the current, and coral reefs offers respite from it, as well as protection from predators. Pauly is also an outspoken critic of bottom trawling, a fishing method in which large nets are dragged across the ocean floor, potentially destroying coral reefs, or anything else in the way. The trouble with trawling "We clearly know the effect of trawling," says Pauly. "It destroys the corals, destroys the fish habitat, and influences negatively the fish populations." He’s not alone. Over the past two years scientists and researchers worldwide have expressed growing concern about deep-water corals.

Canada has been criticized for refusing to support a moratorium on the high seas, although countries that do are in the minority. Conservationists have also urged the government to do more to protect Lophelia and other deep-water corals in its own waters. In 1999, Norway became the first country to regulate activity that could harm its deep-water reefs; its waters are home to the largest known accumulation of Lophelia coral in the world. Five areas are now protected with complete bans on bottom trawling. In Canada, certain coral habitats are also protected with restrictions on some, or all, fishing activity. The Lopheia reef on the Scotian Shelf is a no-fishing zone — no trawlers nor any other fishing gear is allowed there. Search and rescue The problem, says Edinger, is that corals are being destroyed faster than scientists can find and protect them. Although trawlers that operate in non-protected areas are required to report any coral that does come up in their by-catch, by that time at least some damage has already been done. "We’re mapping what is left, as opposed to an intact distribution," says Edinger.

Marty King agrees that while Canada has done a decent job protecting the areas we do know about, more could be done to seek out and protect others. "Over the last ten years, there’s been massive cuts to the DFO’s [Department of Fisheries and Oceans] science programs," says King. "There’s no money to do systematic surveys of areas like seamount, where there might be corals." "There’s virtually no science in a lot of these areas and we don’t know what damage we’re doing to these deep sea habitats which are generally quite sensitive." It’s not just reefs, King says, but a matter of maintaining healthy ocean ecosystems that can sustain abundant life and fisheries. "Our approach has always been to focus on the most sensitive areas first," says King. "Corals are a good example of a species that needs protecting."

|

|

|