| Winds

of change

By Ashley Monckton

OTTAWA

— The winds, they are a changing –

but as wind energy capacities increase throughout Canada,

one scientist says there is a possibility a change in

the winds could mean a change in the climate.

There’s no such thing

as a free lunch

"There isn’t going to be any

technology that’s perfectly clean," professor

David Keith announced to a room full of scientists,

politicians and policy-makers.

|

| Many environmentalists

believe wind power could solve the climate change

problem. |

Keith, a Canada Research Chair in Energy

and the Environment, spoke at a breakfast on Parliament

Hill in September.

He discussed a recent study where he and

his colleagues looked at whether wind power could change

either the regional or global climate.

Keith explained that a field of wind turbines

extracts kinetic energy and alters the wind field, which

could create a change in the climate.

Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences published "The influence of large-scale

wind-power on global climate," last November.

Keith and his colleagues found the ratio

– between the climate changes wind energy was

intended to make, and any unintended climate changes

from wind energy – was significant enough in their

model to warrant a closer look.

|

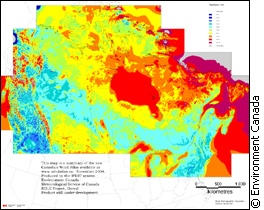

| An atlas of wind speed

across Canada mapping the lowest speeds (blue) to

the highest (red). |

The study used two different general circulation

models – the National Center for Atmospheric Research

model, and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

model.

But Keith said it is important to remember

that coal-fired power is much worse than wind power.

The study also found that the direct climate changes

wind energy caused were beneficial enough to reduce

overall climate impacts.

"We simply have to do more work,"

he said about his results. "If you knew that [the

ratio] was, let’s say, a hundred times bigger,

which is clear the undesirable effects were much bigger

than desirable effects on climate – then that

would be it. Even though it’s a $10-billion industry

- you’d it close down."

Big picture thinker

Keith is a professor in both the department

of economics and the department of chemical and petroleum

engineering at the University of Calgary.

He is also an adjunct professor

at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

and sits on national and international panels that deal

with climate change.

|

| A wind farm in South-East

Ireland, near the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. |

"Everything I do is related to climate

in one way or the other. Either the technologies for

managing the problem, the public policy for managing

the problem, or the science of the problem itself,"

he said.

Joe DeCarolis, a co-author and one of

Keith’s past PhD students, said Keith’s

ability to see the ‘big picture’ is admirable.

"There are probably not enough

people in the world like David who are thinking that

far along the road," said DeCarolis.

But despite his 'big-picture' attitude,

Keith admits the response to his paper has not been

positive: "I was disappointed but not surprised

that people in the environmental community reacted so

negatively."

Whispers in the wind

Some critics have linked the study to

his position in the department of chemical and petroleum

engineering. Keith was quick to point out that the study

was not for that department and that funding came from

the National Science Foundation.

"I don’t work for the

petroleum industry. When I meet my neighbours in Calgary,

and they ask me what I do, I tell them I’m trying

to put them out of business," he said.

| 'When I meet my

neighbours in Calgary, and they ask me what I do,

I tell them I’m trying to put them out of

business.' |

Mark Jacobson, an associate professor

in civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University

in California, is also skeptical of Keith’s findings

– but not because of any perceived ties to the

industry.

"I don’t think the results

in this model prove enough," he said. "It’s

such a rough calculation."

But Keith says that just getting other

scientists, including Jacobson whom he views as an accomplished

atmospheric scientist, to even think about the study

makes it a success:

"Maybe they’ll prove that we

were totally wrong or maybe they’ll prove that

we underestimated the problem."

Keith added we should not only be aware

of our current problems, but also be cautious of any

big, new energy technology.

"I really care about the big wildernesses

in this planet, and we will wreck them if we don’t

manage the problem," he said.

|