|

|

Ideally, the oil industry prefers to extract “light” oil from the ground. Little work needs doing before converting this oil into gasoline or diesel. But bacteria interfere with the process. They biodegrade or break-down the oil hydrocarbon and leave behind viscous material that is hard to work with. Instead of easy-flowing oil, the extraction process now has to deal with “heavy” oil. The oil is so heavy, it resembles the asphalt used to tar roads. “Bacteria eat up the good stuff, and leave behind the heavy viscous oil that is not suitable for the production of gasoline,” says Brij Maini, a professor for chemical and petroleum engineering at the University of Calgary, adding that this was a problem in the oil sands.

Alberta’s oil sands are made up of bitumen, which resembles molasses in consistency, combined with sand, clay and water. “Viscous bitumen was produced by bacterial activity, over the course of millions of years,” says Randy Mikula, Extraction and Tailings Team Leader at Natural Resources Canada. In order to recover bitumen, the reservoir can be subjected to steam-assisted gravity drainage, an extraction technique where steam is injected into the reservoir to loosen the bitumen. “There is quite a bit of energy consumption and release of greenhouse gases in making the steam,” says Maini. “It increases the cost of production as the oil is more expensive to get out.” Currently, around 1.2 million barrels a day are being produced in Alberta, says Mikula, making it all the more important to study if cleaner options are available. Anaerobic bacteria may have a possible role in the production of clean burning methane. Scientists are only recently understanding how these microorganisms work, which can at once be destructive and constructive. It is destructive because bacterial activity thickens the oil and it is constructive because if there is a way for the anaerobic process to be accelerated, it can possibly result in the production of clean methane. How bacteria go about their business Previous studies have suggested that bacteria work in aerobic, or oxygen filled-environments as they chomp down on the oil hydrocarbon. But a recent study published in Nature by scientists from the University of Calgary and the University of Newcastle suggests that bacteria called methanogenic arachea work in anaerobic conditions in petroleum reservoirs. More importantly, the bacteria degrade the oil hydrocarbon to produce methane in a process they have likened to fermentation. Fermentation is a process used to produce many everyday items- starting with beer and bread. For the production of beer, suitable temperatures and anaerobic conditions convert the wort (a combination of different sugars and water) to alcohol and carbon dioxide through the work of yeast. In terms of oil biodegradation, anaerobic bacteria combined with oil and water leads to two resulting steps, according to a press release by the University of Calgary. First, the bacteria produce carbon dioxide and hydrogen, followed by a next step, where they turn the products into methane.

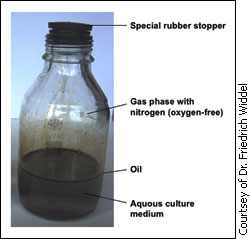

“Methane is a clean energy source,” says Dr. Friedrich Widdel, director of the department of microbiology at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Germany. He is also one of the authors of a previous study of anaerobic bacteria which inspired the latest research coming out of Calgary and Newcastle. “The recent study is targeted to the future,” he says, “Presently there are difficulties to optimize this research, but one should be open to possibilities.” According to the press release, the scientists who worked on the new study suggest that field tests may happen as early as 2009. But Widdel has some reservations. “The activity of these types of bacteria is one of the slowest processes I have ever studied in a lab,” says Widdel, adding it took his team two years to measure the process and get the data. In comparison to the fast-working bacteria lactobacillus which turns milk into yogurt under appropriate conditions, anaerobic bacteria take a while to produce the useful by-products, which include methane. “Yogurt bacteria are like rockets,” he says, “They multiply so quickly they have doubling times of half an hour”. In comparison, the bacteria on oil hydrocarbons have doubling times that are in the order of many days or even weeks, he says. While Widdel says the process may be slow at the moment, he says research should still be pursued in the area. "We should be open to potential, we should be open to the future."

|

|

|