In November, Preseau became one of approximately 500,000

women who are pregnant in Canada each year and must wade

through heaps of ambiguous research, wondering "Is

this safe for my baby?"

|

| Conflicting drug research means difficult

decisions for pregnant women. |

"I never used to think about how everything I did

was affecting me,"says

Preseau, "but now it's all about the baby."

Excited to see a tiny set of 10 fingers and toes in August,

Preseau is trying to avoid exposing her first baby to harmful

substances that could cause birth defects.

Despite her doctor prescribing Diclectin, an anti-nausea

drug used during pregnancy for 40 years in Canada, Preseau

is resistant to join the estimated 80 per

cent of pregnant women who use medication.

| 'A pregnant woman might

say 'I don't want to take anything' but she could be

putting herself and her baby at even more risk' |

"I'm not against it, but if I don't

desperately need it, it's better not to take anything," says

Preseau, who carries blue plastic bags in her wallet for

emergency nausea bouts. "I'll try

everything else before I take medication."

According to Motherisk, a Toronto-based research organization

that counsels pregnant women on drug safety, women and their

doctors must find a balance that will keep the mother healthy

and the developing foetus at the lowest risk.

Motherisk fields about 200 calls each weekday about the

safety of drugs from over-the-counter cold remedies, to prescription

medications for mental illness.

Confusion prevails

With more research accessible than ever why are pregnant

women still hesitant?

"It is very challenging," says Ellen Reynolds,

director of communications for the Canadian Women's

Health Network. "There is a lot of conflicting

information out there."

Barbara Mintzes, an assistant professor in the department

of anaesthesiology, pharmacology and therapeutics at the

University of British Columbia says some scientific studies

are little more than marketing aids and add to the confusion.

"You'll have

huge differences in what different studies might say partly

because it's

an area where there are strong financial interests at play,"

says Mintzes. "For trials sponsored by drug manufacturers,

some that are planned in a way that it's clear the

manufacturer will show an advantage for their drug."

Reynolds also

says memories of the "thalidomide tragedy" make

pregnant women think twice before popping pills.

It's one reason Preseau says she doesn't want

to take Diclectin despite her doctor's recommendation

and supporting research. "I just can't get

out of my mind the thalidomide babies," she says. "They

said 'it's okay' and it turned out it

really wasn't okay."

|

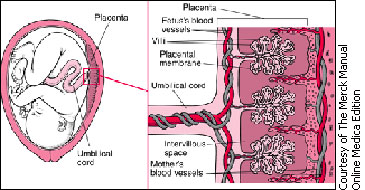

Drugs in the mother's blood can

cross the placental membrane into blood vessels in

the villi and pass through the umbilical cord to the

fetus. |

Reynolds says pregnant women should err on the side of

caution. "With

thalidomide the effects were immediate at birth but with

DES, it was subtle so the effects were only revealed 15 to

20 years later. We can't be sure what we think

is safe actually is," she says, "Precaution

is the only sensible way to go." Thorough, long-term

testing is needed to prevent another medical mistake, she

says.

Finding the balance

While most researchers say pregnant women should be informed

about which medications they use, not all agree that avoiding

medication is the safest bet.

"Not all drugs are thalidomide," says Myla Moretti,

assistant director of Motherisk. She says though using

drugs can be dangerous, "the

most dangerous thing a woman can do is make drastic decisions

out of fear of the unknown ... Sometimes not treating

is more dangerous than treating."

| 'I just can't

get out of my mind the thalidomide babies. They says

'it's okay' and

it turned out it really wasn't okay.' |

"Some

conditions, if left untreated, can put the pregnancy at risk,"

Moretti says. "A pregnant woman might say 'I don't

want to take anything' but she could be putting herself and

her baby at even more risk." Even

if a mom-to-be does everything right, she adds there's

still a three per cent chance to have a birth defect.

Ethical considerations

Another reason why little is known about safe drug use

during pregnancy, says Mintzes, is because researchers are

ethically and legally reluctant to test drugs on pregnant

women. "For

pharmaceutical companies the liabilities are higher for

pregnant women," she says.

|

| Thalidomide is now used in treating

leprosy. |

According

to Moretti, by the time they hit the market, most drugs

have not been tested for safety (or even effectiveness,

adds Mintzes) in pregnancy. This gives women who become

pregnant access to thousands of medications, few of which

have actually been proven safe or effective during pregnancy. Moretti

says medicating is a judgement call that must be made on

a case-by-case basis between a woman and her doctor by balancing

the potential risks with the potential benefits.

Preseau says she is happy to keep her prescription in her

wallet for now right next

to the blue plastic bags.

"You can't believe everything you read, especially

with something so important," says Preseau. "You

just have to take little bits and pieces of information from

everywhere and hope you are doing the right thing."

Front Page Courtesy of The Anti-Stress Blog for Women

|