Tags

Related Posts

Share This

One story. Thirty days. Fifty thousand words.

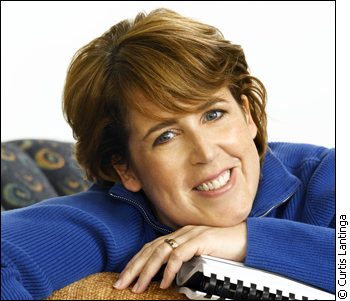

Amidst her whirlwind writing schedule, Kelley Armstrong got an idea: She wanted to write an urban fantasy book for young adults. She had already been a New York Times bestselling author since the seventh book in her Women of the Otherworld series, but with a young adult plotline floating around her mind, she wanted to try something new.

With so many tight deadlines, she wasn’t sure how to fit the new book into her schedule without potentially wasting months if she discovered she wasn’t suited to the young adult genre.

“I couldn’t afford to give up three months or so of my time to find out,” the Aylmer, Ont.–based author says.

Her agent suggested she take part in National Novel Writing Month, an annual challenge for writers everywhere to write 50,000 words in a single month—November. That way, if her book didn’t turn out well, she would have wasted only a month.

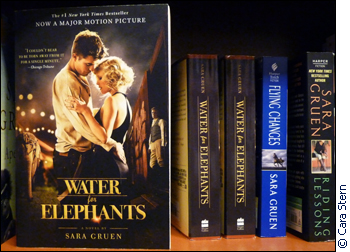

Bestselling book and box office success Water for Elephants began life as a NaNo novel.

She took up the challenge, produced a first draft, and about two and a half years later, released the first book of that new trilogy, Darkest Powers. These young adult books went on to be her most successful, and brought her for the first time to the top spot on the New York Times Best Sellers list for children’s chapter books.

This year, she once again took part in the National Novel Writing Month challenge, affectionately known as NaNoWriMo, and even as NaNo — an appropriate nickname since “nano-” means tiny. Armstrong is among a number of people who have found success through their NaNo novels. Sara Gruen’s Water for Elephants and Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus both began life as NaNo stories.

However, most of the 250,000 participants are not professional writers, but rather use the challenge to try their hand at novel writing. Many don’t ever intend to publish their work.

“One of the purposes of NaNoWriMo is to take novel writing from something you would do one day, to something you would do today,” says Jill Ainsworth, municipal liaison for the Ottawa chapter of the challenge. In her role, she schedules group writing sessions, the kick-off party, and the “thank goodness it’s over” party.

“You give yourself permission to suck, because you’re writing so fast and so much in such a short period of time, and you edit later,” she says, adding that last year, the Ottawa area’s roughly 500 WriMos (as participants like to be called) wrote a total of 15,409,086 words.

Safety in numbers?

Participants gather in coffee shops, libraries, bookshops, and even on the Toronto subway. They can be recognized sitting with their laptops or notebooks surrounded by cups of coffee, often in groups, scribbling away as they try to reach the 1,667 words per day to hit the challenge’s goal.

Ainsworth says writing in a group during the challenge gives WriMos an opportunity to socialize and give each other advice and motivation.

Skeptics remain: ‘We’re in a supercharged media world, and everyone thinks there’s a fast, quick way to do things.’

— writer Seymour Mayne

While it can be nice to write with others, Armstrong warns it can make the challenge more daunting as you see some friends making much faster progress.

“It can have a negative effect of people feeling like they are not accomplishing what they should be,” she says. “The point is not, as far as I’m concerned, to write 50,000 words. It’s to write as much as you possibly can in one month.”

While there are some full-length novels that do end at about 50,000 words, such as The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Armstrong says in general, a complete adult novel is around 100,000 words.

Seymour Mayne, a poet, short story writer, and professor of creative writing at the University of Ottawa, says he’s skeptical of these short-deadline challenges.

“I’m more concerned with the quality of literary work,” he says. “I’d rather somebody take their time and write the book they had to write.”

He acknowledges that these challenges can be useful for some people, but stresses that it shouldn’t be about rushing to skip the hard work.

“We’re in a supercharged media and social media world, and everyone thinks there’s a fast, quick way to do things,” he says. “But I think things have to work out organically.”

Graveyard shift: Toronto WriMos at an overnight “write-in”.

Armstrong says she’s clear that a writer will not produce something publishable within a month, but it’s a good way to test a new idea, and it can get you on the path towards a publishable manuscript.

“What I write in one month is by no means what I would let anyone even see,” she says, explaining that she spends months editing and rewriting her stories but that using NaNo deadlines for the first draft helps speed up the process. “That goes with all of my first drafts.”

There is some debate in the NaNoWriMo community about how agents perceive the challenge. Would they throw away a query letter for a manuscript as soon as they read it was first written in a month?

Sarah Heller, literary agent for the Helen Heller Agency in Toronto, says no.

“For me, when I sign someone on, it’s definitely not unheard of that we work editorially prior to sending out anything to publishers,” she says, explaining that she takes on many new writers, and even represents Armstrong’s young adult series.

However, while it is not necessary to conceal that it was written for NaNo, the fact wouldn’t particularly pique her interest either, she says, and thus is irrelevant on a query letter. She adds, she’s more interested in a good story idea and a letter that shows the author has done research and understands how the publishing industry works.

Stop procrastinating

Drew Beaudoin, the municipal liaison for the Toronto region, says he has been trying to get his 2010 NaNo novel published. He spent months editing it before sending it to one publisher, which gave him his first rejection letter.

Since then, he has continued to edit, and is hoping to send it out to more publishing companies as soon as possible.

“A lot of first-time writers don’t seem to realize it’s just a first draft and you do need to edit it,” he says. “For a NaNo novel, you need to do a complete overhaul of it to bring it up to a publishing standard.”

Kelley Armstrong’s NaNo draft created the Darkest Powers series that made her a #1 New York Times bestselling author.

He says he’s heard of agents receiving a pile of manuscripts as November ends, all from people who finish their novels and send them out immediately.

Heller says she hasn’t noticed a spike in December, but finds more people send in manuscripts in January. She attributes this to people deciding their New Year’s resolution is to finally get their novel published. However, it’s possible that some of these post-New Year’s manuscripts come from WriMos who have spent their winter holidays editing their novel, with a goal to get it to agents in January, Beaudoin says.

Despite the very tight deadline, most people seem to think it’s a good idea to try out the challenge.

“It’s nice to stop censoring and just write,” says Kris Rothstein, an associate agent for the Carolyn Swayze Literary Agency in White Rock, B.C. “I think almost anyone can benefit from the constraints.” However, she adds, it’s good to have put in some thought beforehand.

Armstrong echoes this sentiment; it’s crucial to have an outline so that there’s no time wasted trying to figure out where the story will go. And although she recommends the challenge as a way for would-be novelists to find out if they like writing every day, she recognizes that not everybody will be successful. Still, she says that shouldn’t stop you from pursuing a career as a writer.

“If you can’t do your 50,000 or if you find that writing that fast does not work, never think that means you cannot write,” she says. “If it works for you, great, but if it doesn’t, and you still want to write, find a different way of writing.”