Every month, Oliver Sachgau spends $150 on software, entertainment, and online news subscriptions.

That amount might not seem like much, but for the 22-year-old journalism student, those automatic payments are a sizeable chunk of his $700 monthly income. On top of rent, food, and other expenses, Sachgau often spends more than he earns. Twenty per cent of his monthly budget goes to subscriptions.

Sachgau earns most of his income in the summer months and works part time jobs during the school year. In September 2014, he took out a student loan for the first time to pay for tuition and school expenses. Sachgau has been unemployed since January 2015.

“It’s a source of anxiety. You look at how much money you’re spending and how much you’re earning and it really sucks when you can’t get the first to be less than the second,” he said.

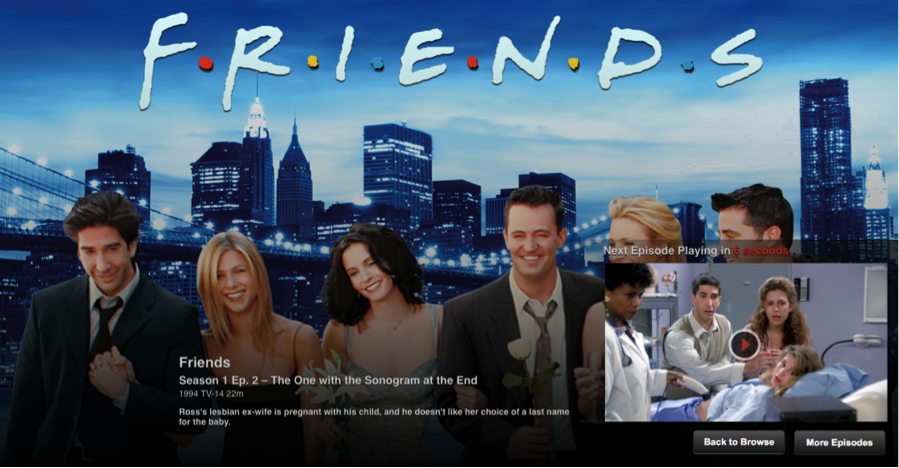

Yet Sachgau can’t just cut back. The young journalist says he needs these services to gain job skills. For example, his $50-per-month Adobe subscription pays for products that are industry standards. He also pays about $100 per month to access the Globe and Mail, Netflix, Microsoft Office 365, and Dropbox Pro.

“If I decided to save that money, I would have lost out on jobs. It’s a short term pain, long term gain sort of thing,” said Sachgau.

Subscribing to a solution

This situation is common among university students, said Murray Baker, author of Debt Free Grad, a personal finance book. Young people often struggle to balance subscribing to necessary services–such as software for schoolwork–and adding costs that don’t provide much value.

“With a lot of students, it’s so easy now to subscribe to a lot of things online. You think, ‘Well here’s five or 10 bucks here.’ It does add up,” he said.

Students should make a plan at the beginning of year that forecasts monthly and one-time expenses against income from a summer or part-time job, said Baker. This approach puts money aside for planned and unexpected expenses. It also shows when a part time job might be needed to cover more expensive months.

The key is to watch when a credit card is used to cover non-essential costs. If each month’s balances are not paid in full, a person is living beyond their means, said Vickie Campbell, a certified financial planner at Ryan Lamontagne in Ottawa.

Overspending every paycheque is unsustainable, so Sachgau must start controlling his expenses. To do this, he should look at what is necessary to get ahead after graduation and what can wait until later.

“You just have to know exactly where you’re spending your money, and then you’ve got to cut those expenses. It’s as clear as that,” said Campbell.

Sachgau’s recent student loan is not necessarily a risk provided he has a repayment plan. Education debt is good debt because it usually leads to increased income, said Campbell.

“No debt is really good, but if it’s going to help you in the future, then it’s some debt you’re going to have to take on,” she said.

Another option to save money is to make a list of each subscription and find ways to get student discounts or free access, said Baker. This won’t remove every cost, but it could get Sachgau closer to breaking even.

Right now, Sachgau is in danger of being unable to afford his lifestyle. The longer he is unemployed, the more expenses he will have to cut.

“If you can’t afford it, you need to find someway in your budget to afford it or maybe you shouldn’t be subscribing,” said Campbell.