Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Urban gorillas and the parkour craze

James Bond attempted it. The Office mocked it. And now, a niche group of mostly teenagers is keeping fit by doing what these fictional characters can’t: vaulting over walls, cat-crawling up railings and leaping from 10-foot drops. This physical movement is called parkour, and its traceurs, or practitioners, combine athletic discipline with animal instinct to negotiate a path around everyday city structures.

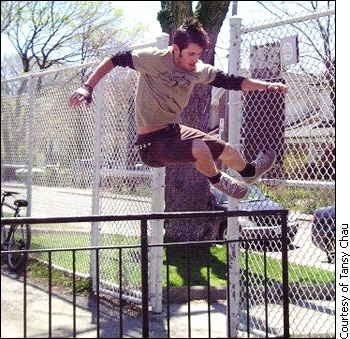

Vaulting a school picnic table in Toronto’s Beaches neighbourhood.

For them, the urban jungle becomes a playground littered with obstacles, and the goal is simple: to move forward as efficiently as possible. Running at a wall to leap it, a traceur jumps, bounds off the wall with one foot and, in keeping with the upward momentum, uses upper-body strength to make the final up-and-over push.

It’s harder than it looks. Casino Royale (2006) featured Daniel Craig’s Bond and his faltering parkour skills as he strove against an antagonist’s smooth manoeuvres; Bond finally resorted to blunt-force tactics such as powering through a still-wet plaster wall instead of swinging through a gap above it. And the well-received TV show The Office parodied the trend in last season’s premiere episode; Michael Scott, Andy, and Dwight amused audiences by somersaulting over couches, trampling across desks and falling into refrigerator boxes. YouTube, as well, has hundreds of thousands of streaming videos made by enthusiasts.

Parkour, then, is the latest craze in popular culture to hit the movies, televison and Internet. Its pioneers, widely credited to be David Belle and Sebastian Foucan, derived the name from parcours du combatant, a phrase that refers to the obstacle courses negotiated by the French military in war-torn Europe. Belle’s father was a soldier, and both founders were teenagers in the 1980s when they began experimenting in the outskirts of Paris.

Parkour has since exploded into the mainstream; MTV launched its “Ultimate Parkour Challenge” last fall where athletes battled for a $10, 000 cash prize. Ottawa has not been left off the map, and Patrick Bériault is here to help the pk scene grow.

Beginnings

Bériault initiated a parkour group that meets twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. As a health promoter for physical activity at the Somerset West Community Health Centre (SWCHC), he says he wanted to engage youth with a cutting-edge sport. To capture attention and attract participants, he bills the program as an extreme activity.

“My legs are aching the next day whenever I’m done, but it’s not extreme in the sense that we’re leaping across buildings and running among cars,” says Bériault.

The program, now in its second year, focuses on conditioning and teaching the essential body movements. With a background in kinesiology, Bériault leads sessions to strengthen muscles and quicken agility. Fast footwork and the ability to tumble can help prevent injury, he says, because the kids will be able to recover if a slip or a mishap occurs.

Patrick Bériault explains proper front-roll technique at a Gatineau training session.

“Parkour is as dangerous as you want it to be,” says Dan Iaboni, the whizz kid behind both the popular go-to website, pkTO.ca, and the unique indoor training centre known as the Monkey Vault in Toronto. “If you want to be perfectly safe, you can do parkour perfectly safe, because 99 per cent of the stuff is on the ground and the biggest problem you’re ever going to get is maybe a banged-up knee, bruises on your arm or a little cut or scratch.”

Sprained ankles are the most common injury in parkour (but even so are rare). Traceurs must understand their limits, Iaboni explains. Newcomers cannot simply go out, pretend they are Superman and copy a YouTube video.

Moving within the law

Perhaps due to the occasional reckless kid, parkour suffers ill repute among authorities. Security guards and law-enforcement officers are sometimes less than thrilled with the public activity.

‘We’re not doing anything wrong. It’s not illegal to jump down a set of stairs instead of walking them.’ – parkour organizer Dan Iaboni

“Especially in the financial district, security guards are always trying to kick us out left and right. People complain inside, and they don’t want us on the property,” says Iaboni. In that case, he explains, traceurs will leave and move to the next building.

Seventeen-year-old Juan Diego practised parkour in Ottawa for several months and sees disapproval as an overreaction. He says, in Canada especially, authorities should pause long enough to confirm the need for any interference.

“In Colombia, if they see you climbing something, they immediately think you stole something. So they call the police,” says Diego.

The key is to ask permission before using the property, says Ottawa police spokesman Const. J.P. Vincelette. If traceurs fail to do so or choose to disregard the owner, they could be charged with trespassing. To date, Ottawa police do not have parkour flagged as a problem.

Says Iaboni, “We don’t have skateboards. We’re not marking stuff up. We don’t have spray paint in our hands. We’re not doing anything wrong. It’s not really illegal to jump down a set of stairs instead of walking them.”

Gaining momentum

The SWCHC group, comprised of 8 to 10 members during the summer peak season, often trains at Place du Portage in Gatineau and in downtown Ottawa — two hotspots for traceurs, because both locations provide creative possibilities. Intricate architecture, cement structures, benches and railings are all ideal to stimulate expression. These weekly meet-ups are as formal as parkour gets in Ottawa. The nation’s capital has yet to see the level of organization and enthusiasm that is visible in Toronto.

Toronto’s Monkey Vault, for instance, opened its doors in 2008 and continues to thrive as a community project. There are about 15 people who train every day and about 150 to 200 others who visit each month. It’s the only gym of its kind in Canada, designed with parkour specifically in mind.

Iaboni’s website, similarly, is a hub for enthusiasts to connect and to organize meets. More than 700 people visit the site at least three times a month, and Iaboni estimates 300 check it every day.

Iaboni says the city of Toronto sees about 60 different meet-ups in the summer. Popular places to train include the financial district, the University of Toronto, the city hall area and the downtown park Cloud Gardens.

No obstacle is too big for traceur Max Lee Fox Stussi at Toronto’s Malvern Collegiate Institute.

At a training session, it’s not uncommon to drill a jump until the timing, body position and landing are perfected. If a structure becomes familiar to the point that its ins and outs are known by heart, the movement becomes instinctive.

Iaboni likens this second nature to someone who starts dancing when music is turned on. “They do whatever they feel like inside, and that’s what we do, too. We’re outside, we see a bunch of stuff and your body takes over.”

The leap to the future

In light of Canada’s good showing at Vancouver’s Olympics, could parkour have a future in international sport? Iaboni insists parkour is not about competition, despite the excitement over MTV’s Ultimate Parkour Challenge in the U.S. The culture in Canada is more oriented to building camaraderie and helping one another. Training in big groups, especially, provides the chance to exchange knowledge, ask questions and fine-tune skills.

“I’d like to see as many as possible doing it. Everyone used to do this stuff as a kid and everyone sort of grows out of it. I don’t believe people should grow out of it. Everyone should be moving and running around,” says Iaboni.

Related Links