Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Ottawa poets hit a grand ‘slam’

The stage is set. The lone microphone stands in front of the red velvet curtains, visions of Ottawa’s Byward Market creeping in between the cracks of the drapes. The glittering disco ball hangs high above, its soft, shimmering lights bouncing off the surfaces of the room.

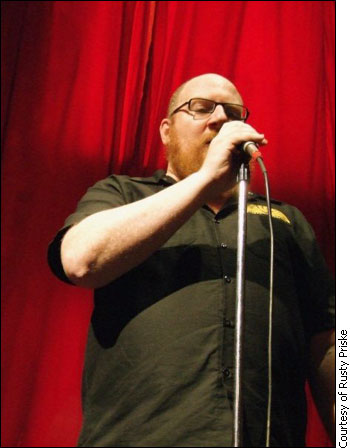

Rusty Priske steps onto the stage. His smiling face is encased by a substantial red beard and set off by a pair of thick, black-framed glasses. His huge boots and ample frame take charge of the small stage. He looks out into the room, and every pair of eyes is staring right back at him.

The audience has filled the Mercury Lounge’s small venue to the brim. People sit on chairs, tables, the floor, even other people. Everyone is welcome: young and old, suits and students, old favourites and first-time performers. The raucousness of the crowd falls into a single cry of “Raise it!” as all fists rise to the air and fall, into a dead silence of anticipation.

Burly bard: Rusty Priske performs at the Mercury Lounge.

Priske closes his eye, takes a step back from the microphone, and begins.

To many, the scene would announce a rock concert over a poetry reading. But this is the newest addition to Ottawa’s arts landscape: slam poetry.

Ottawa’s thriving slam poetry scene brings in audiences from all walks of life and consistently sells out shows. Each performer’s passion and individuality inspire a following. Crowds seem devoted to their favourite poets, and the art form flourishes by virtue of the sheer diversity of poets that Ottawa has to offer.

A slam is one part poetry reading, one part competition. But the host is always quick to remind the performers that “the points aren’t the point; the poetry is the point.”

There is room for 12 slam performers to sign up; each has three minutes to perform a poem. Five random audience members are chosen to be judges, and their scoring determines the evening’s winners. The five poets with the highest scores then move on to the next round. Those five poets then each perform again, and the judges determine the winner of the night.

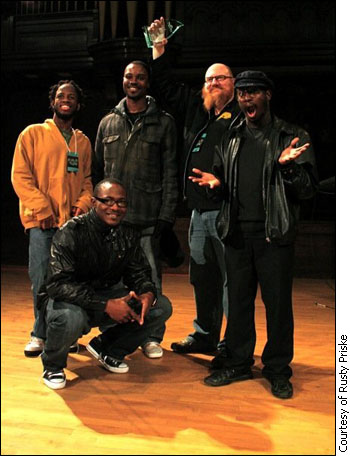

The nightly winners’ scores are recorded, and at the end of the season the poets who had the five highest scores make up the team that represents Ottawa in the national slam competition at the Canadian Festival of Spoken Word. Last year, Ottawa took first place out of 11 teams from across Canada.

And Ottawa said… Let there be slam

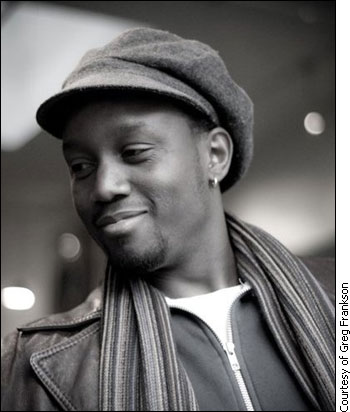

Ottawa’s first show dedicated entirely to slam poetry was Capital Slam, which premiered in October 2004. Local poets Elissa Molino and Greg Frankson (who goes by the pen name Ritallin) started Capital Slam. It is now one of Canada’s longest-running poetry slam series.

Frankson says he began performing spoken word poetry in 2003 as a natural step from writing hip hop. “All music is, is poetry to a beat,” says Frankson. He says he was frustrated at having only one venue, The Gold Star Lounge at the African Palace, which would occasionally host poetry slams.

“We thought we could do a pure slam, and that would provide a place for people to practise and to get better,” says Frankson.

Frankson says the first few slams had fairly small crowds, but by the end of the first season they were selling out shows. What started as a monthly show now runs every two weeks because of slam’s popularity with both performers and audiences. Now, along with the Mercury Lounge, Umi Café also has an ongoing slam poetry series, and Avant-Garde Bar and Café Nostalgica have also hosted poetry slams.

‘Raise it!’ the crowd shouts. All fists rise and fall, into a dead silence of anticipation.

Local poet Rusty Priske is the slam master for this season of the Capital Slams. He organizes the slams, and irons out the fine details of making sure everything runs smoothly. Although he went to his first slam only a couple of years ago, he has already made a name for himself in Ottawa’s poetry scene and was part of Ottawa’s team that won at last year’s national competition.

“Right from the first show, I was hooked,” says Priske. He says he was just blown away by the poets he saw at his first slam: people like Steve Sauvé, John Akpata and Kevin Matthews. He says he was moved by what they were doing, but also saw that that connection with the audience was something he could achieve, too.

“I was just taken by what the possibilities were,” he says. “This is just cool.”

Priske says that the Ottawa scene is unusual because it maintains so many different styles. He says that sometimes he sees cities that get their own style, which is distinct and interesting but may influence the way new poets find their own voices. For example, he says, Montréal has a strong musical strain. But at any given Capital Slam show there is a mix of people — from classical poetry backgrounds and hip hop backgrounds, lyrical romantics and political activists

Frankson agrees. He says that the poets are varied, so they bring in varied audiences: “Young professionals, public servants sitting alongside the goths and the hippies. Everybody comes.” This diversity, Frankson says, is what keeps the scene strong and growing.

Greg “Ritallin” Frankson can stimulate audiences’ brains.

At the Capital Slams, performers seem mostly to fall between ages 25 and 40. But the show is all ages; the audience consists of everyone, from teens to people who probably have teenaged grandchildren.

The long and the short of slam

The history of slam starts with Marc Kelly Smith and the Uptown Poetry Slam at the Green Mill in Chicago in the 1980s. It was all about trying something new, taking performance to the next level, having fun, but most of all was about opening up poetry to everyone. Smith says that at the time in Chicago, average poetry shows would draw in 15 people at most, and were “staid, formal, and really quite boring.”

Smith says, “The show’s always been a place where you can push the boundaries of what poetry was meant to be.” The stage of the Green Mill has been graced with everything from classical forms of poetry to group sketches to a 78-year-old woman reciting poetry while performing yoga exercises.

The name “slam poetry” came from Smith watching a Chicago Cubs game. The phrase “grand slam” kept coming up, which brought “slam dancing” to mind and all the energy and power that those ideas contain. He says he was also unsure about whether or not the shows would be a success, so he also liked the idea of calling them slams because “it could be a grand slam, or it could be that we’ll slam the door in your face.”

Since Smith’s first show, in 1984, slam has spread across North America and through Europe as well. Smith says that time and again, he sees people come to one of his slams and then go home and start their own shows that become immensely popular.

But a boys’ club?

Although there is always a level of diversity in the scene, Priske points to the lack of female poets coming to perform at the Ottawa slams. There are usually only one or two female participants per show of 12 performers or more.

Danielle K.L. Gregoire has been a poet in Ottawa for years and one of the first slam masters of Capital Slam. She now lives in Lanark County and organizes the Lanark County Live Poets Society (LiPS). She says there used to be more female performers in Ottawa, but recent seasons have seen fewer and fewer.

“It seems like a self-fulfilling prophecy,” says Gregoire. “The less we see ourselves represented on stage, the less likely women are to get up there.”

‘Young professionals, public servants sitting alongside the goths and hippies. Everybody comes.’ — poet Greg Frankson

Josie Frank just started performing slam poetry this year and says that although she has felt comfortable and safe entering the scene, there have been very few female role models. She says that this could be a result of the type of confessional poetry many women write.

“In my experience, the political poetry tends to receive higher scores, and not many female poets perform political pieces,” says Frank.

This male predominance notwithstanding, Ottawa’s slam poetry scene has grown exponentially. Five years ago, local poets only had one monthly chance to perform; now there are usually eight or nine monthly opportunities to perform at different shows in the Ottawa area. Poets from the original slams now run their own shows across town, and the inspiration from the old poets drives an influx of new poets.

“Our poets continue to flourish because of all those opportunities to practise and get better,” says Frankson.

Ottawa’s national slam team (from left: Brandon Wint, Komi Olafimihan, Ikenna Onyegbula, Rusty Priske, Ian Keteku).

A cycle of poetic inspiration

Apart from a Facebook group, the Capital Slam does no promotion. The shows sell out time after time from word of mouth. Priske says, “People know about it; they want it, and I don’t see an end to that.”

Karl Roth, 21, is a university student and a first-time audience member. He says he heard about slam through a friend and decided to sample a Mercury Lounge show.

“It was a great experience; I’ll definitely go back,” says Roth. Although he probably would never perform himself, he says he really enjoyed the show’s relaxed atmosphere and enjoyed the poetry more than he expected.

Priske says that it comes down to getting new people interested and new poets involved. “Once [somebody] goes to one, they walk away with that one thing that they remember,” he says.

The year 2010 promises to be an even bigger year for spoken word, as Ottawa has been chosen to host The Canadian Festival of Spoken Word. Ottawa’s new team will have to defend their title against competitors from all over the country.

But as Frankson says, “The future is bright.”

Related Links