Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Quartier Vanier: nowhere to go but up?

At the east end of Cummings Bridge, minutes from downtown Ottawa, a sign at the corner of Montreal and North River Roads announces, in elegant 17th-century-style typeface, your arrival in Quartier Vanier.

The “Quartier” moniker is a recent addition to the traditional “Vanier,” part nod to the area’s largely francophone roots, part re-branding effort for a neighbourhood of the nation’s capital widely seen as down on its luck.

A good sign? Vanier’s entry points now sport handsome boundary markers, courtesy of the local Merchants Association.

Influenced by sensationalist media stories, many Ottawa residents have come to view Vanier as synonymous with problems such as crime, homelessness, prostitution and drug abuse.

These days, however, Vanier seems to be going through a renaissance of sorts. Though still plagued by social and reputation issues, the area is also seeing gentrification as people gauge the potential of Ottawa’s most notorious ’hood.

Residential property sales prices are up almost 20 per cent this year, according to Roch St-Georges, a real estate agent specializing in Vanier. “I was very surprised by the increase in selling price in the Vanier area,” St-Georges said, explaining that many clients are tearing down older houses to replace them with new ones. “There’s definitely a turn-around happening. It will take time, but it is definitely on the right track.”

Young professionals with families are flocking to the neighbourhood, due in large part to its continued affordability and proximity to the downtown core. With the recent gentrification of the Hintonburg area, Vanier now stands as the final major downtown neighbourhood to undergo urban renewal. City of Ottawa statistics indicate rising rent costs, along with a growing population. Developers are also investing in the area, constructing multi-unit properties in hopes of profiting from Vanier’s newfound trendiness.

On the cultural front, there have been positive steps as well. Montreal Road, the community’s beleaguered main artery, is being cleaned up. Alongside the pawnshops and payday loan businesses, new restaurants and shops—Bobby’s Table and Bridgehead, for example—are opening, and improvements are being made to existing structures.

‘There’s definitely a turn-around happening. It will take time, but it is definitely on the right track.’ – Roch St-Georges, real estate agent

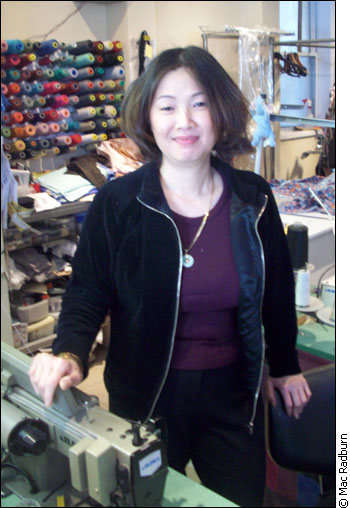

Lang Chi Dang, the owner of Fantastic Tailors and Cleaners on Montreal Road, recently had the facade of her business completely re-done in stucco, at great expense. She says with all the positive changes in the community, her investment will pay off and could inspire others to follow suit.

Street appeal is a high priority for Dang. She says in the past, customers would express safety concerns about walking from their cars to her business. “If you drive by and you see something that makes you feel insecure, you wouldn’t stop your car and step out,” Dang said. She added, “We’ve had problems. Sometimes people come to ask for money, and there’s prostitution,” she said. “Right now there is less and less.”

Ottawa Police Service statistics reflect what neighbourhood residents already know—today’s Vanier is a safer place to work and live than the Vanier of the past. News stories from the Vanier area historically dominated Ottawa media crime coverage. Past police figures indicated more Vanier criminal activity than the city average, with less than half of all Vanier residents reporting that they felt safe when walking alone at night.

The situation has improved in recent times, however, with crime rates declining steadily since 2006, and total Criminal Code offences dropping 10.2% in Vanier in 2009. Residents also report seeing less blatant criminal activity on side streets and along Montreal Road.

Local business owner Lang Chi Dang is pioneering the neighbourhood revival.

The largest change to this stretch of road is still to come, when the Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health completes its expansion plans for a 25,000-square-foot building (conceived by famed architect Douglas Cardinal, who designed the Canadian Museum of Civilization). To be built atop and around the existing Wabano building at Montreal Road and Altha Avenue, the new structure will serve as a Vanier landmark and completely change the streetscape, says Carlie Chase, the center’s director of initiatives. Featuring natural materials and undulating panels of glass, the $14 million-plus centre will lend itself to the revitalization of Vanier, providing valuable services and sparking further gentrification, says Chase. “It has a ripple effect. We certainly anticipate [that] the beauty of this centre—and the heart of this centre and the service impact this centre will have—will change the entire community.”

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, the area around the centre’s future location seems ready and reflective of positive change. The sidewalks bustle with residents and passersby. People enjoy an outdoor drink on a pub patio, while multiple construction crews are busy installing new stucco facades to buildings. Then, without warning, a man on the sidewalk sways violently as he throws a cigarette butt to the ground. After an extended fumbling with his belt buckle, he undoes his pants and urinates on one of the storefronts, seemingly oblivious to passing pedestrians and cars.

In response to community complaints over similar incidents and concerns over crime, the Quartier Vanier Merchants Association has launched several initiatives over the past few years to improve safety and livability. Beautification and graffiti-removal programs have been initiated and a farmers’ market started, and regular foot patrols take place with hired security services and the Ottawa Police Service.

A nice facade. This newly re-stuccoed building, hosting a family restaurant and a gentlemen’s club, typifies Vanier’s duality.

Still, despite the many signs of positive change in the area, residents and community leaders seem to temper their optimism as they grasp the challenges the community must unite to overcome. “There are barriers to change,” says Rideau-Vanier city councillor-elect Mathieu Fleury, who, in the October 2010 municipal election, defeated longtime incumbent Georges Bédard. Seen by many commentators as the face of the new Vanier, Fleury must find a way to balance the tensions between old and new, to successfully usher in future change.

Some Vanier constituents have already come to him with concerns over condominium developments, such as those on Landry Street, aimed at hoped-for middle-class residents. “Although people are in agreement with intensification, they do not want to see 20- and 30-storey buildings being built in the middle of residential communities,” Fleury said.

Indeed, the opening of new shops and restaurants, the perception that social problems are on the decline, the influx of new residents and the construction of trendy condos have some boosters pegging Vanier as the “next Westboro.” Though Fleury takes such remarks as a compliment, he says that Quartier Vanier will forge its own distinct path.

“There needs to be investment, there needs to be a facelift on main arteries and there needs to be community involvement through all of this. But it will be Vanier’s way—not another Westboro.”